Sterilization Standards: When to Use Heat, Steam, or Alternatives

Posted by Admin | 25 Dec

What it means when sterilization standards require the use of heat, steam, or validated alternatives

Many regulated environments (healthcare reprocessing, medical device manufacturing, laboratories, and certain food or pharma applications) interpret sterilization as a validated process that consistently achieves a defined microbiological safety target. In practice, that is why sterilization standards require the use of heat steam or other validated sterilization technologies: the method must be controllable, repeatable, and provably effective for the intended load.

A common benchmark used in device and pharma contexts is a sterility assurance level of 10-6, meaning the probability of a viable microorganism surviving is at most one in a million for a validated process. Whether your sector uses that exact criterion or a different acceptance approach, the underlying expectation is the same: a documented cycle, measurable critical parameters, and routine monitoring that demonstrates ongoing control.

Sterilization vs. disinfection (why the distinction matters)

Disinfection reduces microbial load; sterilization aims to eliminate all viable microorganisms, including resistant bacterial spores. If your products or instruments contact sterile tissue, bloodstream, implants, or critical manufacturing zones, standards typically push you toward steam, heat, or another validated sterilization modality rather than “high-level disinfection.”

Steam sterilization (autoclave): the default standard when materials can tolerate moisture

Steam is widely favored because it transfers heat efficiently, penetrates porous loads when properly packaged, and can be monitored with clear physical and biological evidence. Typical saturated-steam cycles include 121 °C for ~15 minutes (often gravity displacement) and 132–134 °C for ~3–5 minutes (often pre-vacuum), with additional time for come-up, exposure, and drying depending on the load configuration.

Critical parameters you must control

- Temperature and exposure time at the load location (not just in the chamber)

- Steam quality (adequate dryness fraction; minimal non-condensable gases)

- Air removal and steam penetration (especially for porous packs and lumens)

- Drying performance to avoid wet packs, wicking, and recontamination

Routine monitoring that auditors expect to see

A practical, defensible monitoring stack includes: (1) physical records (time/temperature/pressure printout or electronic log), (2) chemical indicators inside each pack (and process indicators on the outside), and (3) biological indicators (BIs) on a defined schedule and in high-risk loads. For implant loads, many programs require a BI in every load and quarantine until BI results are acceptable.

If you routinely process lumened devices, include a challenge device (or manufacturer-recommended process challenge) that represents the hardest-to-sterilize pathway. The goal is to demonstrate steam penetration where failures are most likely to occur.

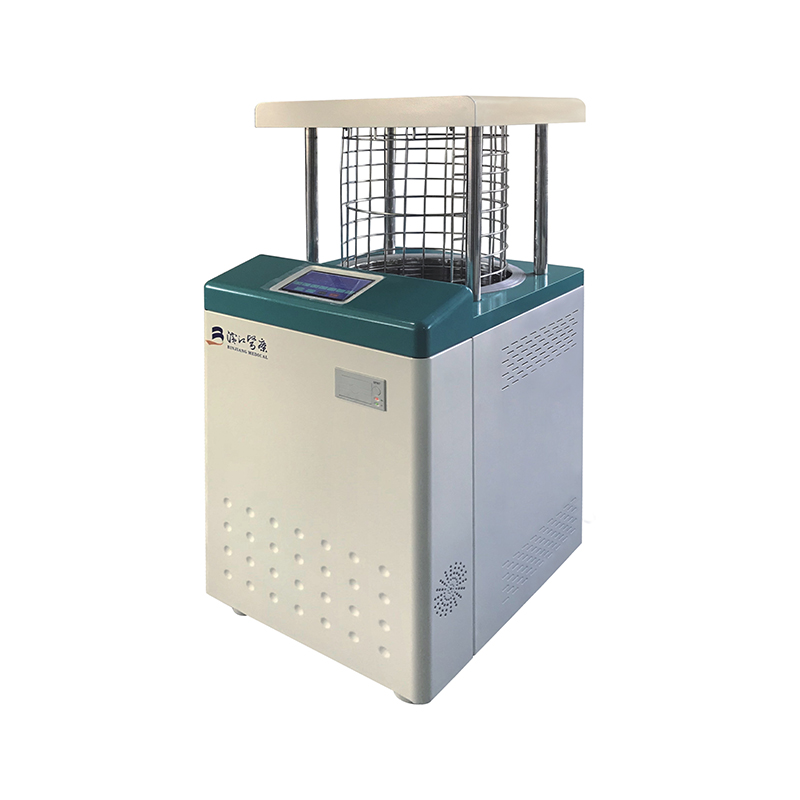

Dry heat sterilization: when “heat” is required and moisture is a problem

Dry heat is useful for items that may corrode, dull, or degrade in moist conditions (for example, certain powders, oils, or moisture-sensitive components). It typically requires higher temperatures and longer exposure than steam because air transfers heat less efficiently.

Common dry-heat parameters used in practice

- 160 °C for ~2 hours (typical reference point for many dry-heat sterilization applications)

- 170 °C for ~1 hour (higher temperature, reduced exposure)

- 180 °C for ~30 minutes (fast cycle for compatible loads)

Dry heat is also used for depyrogenation in pharmaceutical contexts, often at substantially higher temperatures than sterilization alone, when the objective includes endotoxin reduction. If your requirement includes pyrogen control, you must validate specifically for that endpoint rather than assuming “sterile” implies “apyrogenic.”

Operational pitfalls to avoid

- Overloading trays, which creates cold spots and uneven exposure

- Using packaging that insulates or is not rated for the selected temperature

- Failing to map load temperature (assuming chamber temperature equals load temperature)

When steam or heat will not work: validated low-temperature “or” options

Standards and auditors generally accept alternatives when you can justify material compatibility and validate the process to the same sterility expectations. Typical low-temperature options include vaporized hydrogen peroxide (VHP) or hydrogen peroxide gas plasma, ethylene oxide (EtO), and radiation for certain manufactured products.

| Method | Typical operating range | Strengths | Constraints to plan for |

|---|---|---|---|

| Steam | 121–134 °C, moist heat | Fast lethality, strong penetration when packaged correctly | Not suitable for moisture/heat-sensitive materials; drying failures can create wet packs |

| Dry heat | 160–180 °C, dry air | Moisture-free; useful for certain powders/oils and heat-stable components | Long cycles; risk of uneven heating; limited compatibility for plastics and adhesives |

| VHP / H2O2 plasma | Low-temp cycles (often <60 °C) | Good for many heat-sensitive devices; no long aeration tail | Material and lumen limitations; packaging must be compatible; cycle load configuration matters |

| Ethylene oxide (EtO) | Low-temp gas with humidity control | Excellent penetration; compatible with many complex devices and materials | Toxic residues; requires aeration; longer overall turnaround; stricter environmental controls |

| Radiation (manufacturing) | Validated dose (kGy-based) | High throughput for packaged goods; no high heat | Material aging/discoloration risk; requires dose mapping and product-specific validation |

A practical method-selection rule

Use steam when the device and packaging can tolerate moisture and temperature; use dry heat when moisture is unacceptable and the load is heat-stable; choose a validated low-temperature process when material compatibility, electronics, adhesives, or dimensional stability prevents heat/steam use. Document the rationale as part of your quality system so the “or” choice is traceable and defensible.

Validation and documentation: how to prove you met the standard

Sterilization failures are often traced back to weak validation or incomplete routine controls rather than the technology itself. A robust approach ties the cycle to the real-world load configuration and demonstrates repeatable success under worst-case conditions.

What a defensible validation package typically includes

- Installation and operational checks (equipment installed correctly; sensors and controls function as intended)

- Performance qualification using representative and worst-case loads (including the hardest-to-sterilize device pathways)

- Defined acceptance criteria (e.g., BI results, cycle parameter limits, and package integrity outcomes)

- Change control triggers (new packaging, new device design, new load pattern, maintenance affecting heat/steam delivery)

Records that prevent common audit findings

- Cycle printouts or electronic logs retained per policy, with review and sign-off

- Lot or load traceability: which items were in which cycle, with indicator results

- Calibration and maintenance history for critical sensors and controls

- Nonconformance reports and corrective actions when indicators or parameters fail

Operational checklist: reducing failures in day-to-day sterilization

The most expensive breakdowns are usually preventable process-control issues. Use the checklist below to align daily practice with the expectations behind heat/steam-or-alternative requirements.

Load preparation and packaging

- Avoid overpacking; ensure pathways for steam or hot air circulation

- Use packaging validated for the method (steam-permeable wraps for steam; temperature-rated materials for dry heat)

- For lumens, follow manufacturer instructions on adapters, flushing, and challenge devices

Cycle execution and monitoring

- Confirm the correct cycle is selected for the load category and packaging

- Place internal chemical indicators in the most challenging location within each package

- Use biological indicators per policy, and treat any BI failure as a controlled event requiring investigation

- Review cycle charts for parameter excursions; do not rely on “cycle complete” alone

Post-cycle handling (often overlooked)

Wet packs, torn wraps, or rushed cooling can negate an otherwise acceptable cycle. A strong operational control is to require that items are dry and packaging is intact before release, and to store sterile goods under conditions that protect package integrity. A useful internal quality rule is: if the barrier is compromised, sterility cannot be assumed.

English

English русский

русский Français

Français Español

Español Indonesia

Indonesia Deutsch

Deutsch عربى

عربى 中文简体

中文简体