What is a Chemical Indicator? Types, Uses & How They Work

Posted by Admin | 16 Feb

A chemical indicator is a substance that changes color or other observable properties in response to specific chemical conditions, such as pH levels, temperature changes, or the presence of particular compounds. These materials serve as visual signals that allow scientists, medical professionals, and industrial workers to monitor chemical reactions, detect contamination, or verify sterilization without requiring complex instrumentation.

Chemical indicators work through molecular transformations that produce visible changes. When exposed to target conditions—whether acidic solutions, high temperatures, or oxidizing agents—the indicator's chemical structure alters, typically resulting in a distinct color shift that can be observed immediately. This simple yet reliable mechanism has made chemical indicators indispensable tools across laboratories, hospitals, food production facilities, and manufacturing plants worldwide.

How Chemical Indicators Function

The fundamental principle behind chemical indicators involves reversible or irreversible molecular changes triggered by environmental factors. Most pH indicators, for instance, are weak organic acids or bases that exist in different colored forms depending on whether they're protonated or deprotonated. When the hydrogen ion concentration changes, the equilibrium shifts between these forms, producing observable color transitions.

Take phenolphthalein as a classic example: this compound remains colorless in acidic and neutral solutions (pH below 8.2) but turns vivid pink in basic conditions (pH above 10.0). The transition occurs because the molecular structure rearranges in the presence of hydroxide ions, creating a chromophore—a part of the molecule responsible for color—that absorbs light differently than its acidic counterpart.

Temperature-sensitive indicators operate through different mechanisms, often involving phase transitions, polymerization reactions, or the breakdown of chemical bonds at specific temperatures. These materials are engineered to respond within precise temperature ranges, making them invaluable for monitoring sterilization processes that require temperatures between 121°C and 134°C for effective microbial elimination.

Major Categories of Chemical Indicators

pH Indicators

pH indicators represent the most widely recognized category, used to determine the acidity or alkalinity of solutions. These substances undergo color changes at specific pH values, with each indicator having a characteristic transition range:

| Indicator Name | pH Range | Color Change | Common Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Methyl Orange | 3.1 - 4.4 | Red → Yellow | Strong acid titrations |

| Bromothymol Blue | 6.0 - 7.6 | Yellow → Blue | Neutral point detection |

| Phenolphthalein | 8.2 - 10.0 | Colorless → Pink | Base titrations |

| Universal Indicator | 1 - 14 | Red → Purple | General pH screening |

Redox Indicators

Redox (reduction-oxidation) indicators change color based on the oxidation state of the solution. These are essential in titrations involving electron transfer reactions. For example, potassium permanganate serves as a self-indicator in redox titrations, transitioning from intense purple to colorless when reduced, signaling the endpoint when all oxidizing agent has been consumed.

Thermochromic Indicators

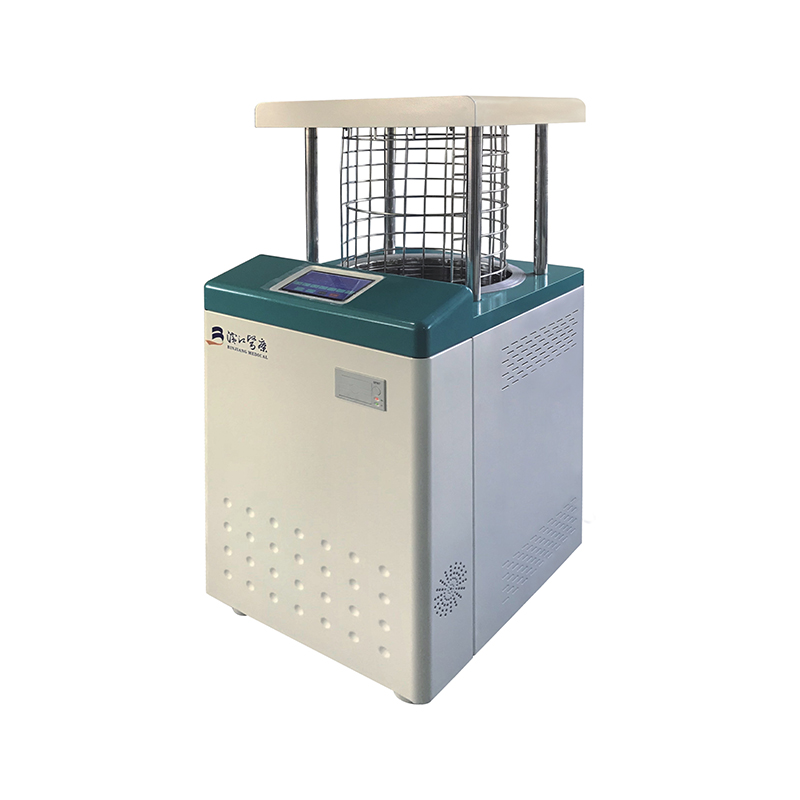

Temperature-responsive indicators find extensive use in sterilization monitoring and quality control. In medical settings, autoclave indicator tape contains chemical stripes that change from tan to black when exposed to steam sterilization conditions, providing immediate visual confirmation that instruments have undergone the sterilization cycle. These indicators don't guarantee sterility but confirm exposure to appropriate conditions.

Complexometric Indicators

Used primarily in EDTA titrations for determining metal ion concentrations, complexometric indicators form colored complexes with metal ions. Eriochrome Black T, for instance, binds with calcium and magnesium ions to produce a wine-red complex, which turns blue when EDTA displaces the indicator, signaling the titration endpoint in water hardness testing.

Practical Applications Across Industries

Laboratory and Research Settings

Chemical laboratories rely heavily on indicators for analytical procedures. In acid-base titrations, which determine unknown concentrations with precision often exceeding 99.5% accuracy, the correct indicator choice is critical. The indicator's transition range must overlap with the equivalence point pH to ensure sharp, visible endpoints that minimize measurement error.

Biochemistry laboratories use pH indicators in buffer preparation and enzyme activity studies. Many enzymes function optimally within narrow pH ranges—pepsin, for instance, requires pH 1.5-2.5 for maximum activity—making continuous pH monitoring essential for experimental reproducibility.

Healthcare and Sterilization

Medical facilities use biological indicators and chemical indicators as complementary sterilization verification systems. While biological indicators contain bacterial spores to confirm actual sterilization, chemical indicators provide immediate feedback on process parameters. The FDA recognizes six classes of chemical indicators, from simple process indicators (Class 1) to advanced integrating indicators (Class 5) that respond to multiple sterilization parameters simultaneously.

Diagnostic testing also employs chemical indicators extensively. Urine test strips contain multiple indicator pads that detect glucose, protein, pH, and other markers through color changes, enabling rapid preliminary diagnoses. These strips use enzyme-coupled reactions and pH-sensitive dyes to screen for conditions ranging from diabetes to urinary tract infections.

Food and Beverage Industry

Food safety monitoring relies on indicators to detect spoilage and contamination. Intelligent packaging incorporates pH indicators that respond to volatile amines and other compounds released during protein decomposition, changing color when meat or fish spoils. Research shows these indicators can detect spoilage 24-48 hours before visible signs appear, reducing foodborne illness risks.

Brewing and winemaking operations use pH indicators to monitor fermentation processes. The pH of fermenting beverages affects yeast activity, flavor development, and microbial stability, making regular monitoring essential for consistent product quality.

Environmental Monitoring

Water quality assessment employs chemical indicators to evaluate pollution levels and treatment effectiveness. Pool and spa maintenance relies on chlorine test strips containing DPD (N,N-diethyl-p-phenylenediamine) indicators that react with free chlorine to produce pink coloration, with intensity correlating to sanitizer concentration. Proper chlorine levels (1-3 ppm for pools) are essential for pathogen control while avoiding irritation.

Selecting the Appropriate Indicator

Choosing the right chemical indicator requires understanding several critical factors:

- Transition range compatibility: The indicator's color change must occur at or near the expected endpoint or target value

- Color change distinctiveness: Sharp, easily distinguishable color transitions improve detection accuracy

- Sensitivity requirements: Some applications demand indicators that respond to minute changes, while others need broader detection ranges

- Environmental stability: Temperature, light exposure, and interfering substances can affect indicator performance

- Safety considerations: Some indicators are toxic or carcinogenic, requiring appropriate handling protocols

For titrating a strong acid with a strong base, the equivalence point occurs at pH 7, making bromothymol blue or phenol red suitable choices. However, when titrating a weak acid with a strong base, the equivalence point shifts to pH 8-9, requiring phenolphthalein instead. Using the wrong indicator can result in endpoint detection errors exceeding 5-10% of the true equivalence point.

Limitations and Considerations

While chemical indicators offer convenience and immediate results, they have inherent limitations that users must recognize:

Precision constraints mean chemical indicators typically provide semi-quantitative or qualitative results. A pH indicator might distinguish between pH 5 and pH 7, but electronic pH meters offer accuracy to ±0.01 pH units. For critical measurements requiring high precision, instrumental methods remain superior.

Interference from colored solutions, turbidity, or other chemicals can mask indicator color changes or produce false readings. Samples containing transition metals, organic dyes, or high ionic strength may require dilution, filtration, or alternative testing methods.

Temperature effects alter indicator behavior, as transition ranges shift with thermal conditions. Many pH indicators show 0.01-0.02 pH unit changes per degree Celsius, potentially affecting results in applications involving temperature fluctuations.

Storage and shelf life considerations impact reliability. Chemical indicators degrade over time when exposed to light, air, or moisture. Expired indicators may show diminished color changes or altered transition points, compromising result validity. Proper storage in dark, cool, dry conditions and adherence to expiration dates ensures consistent performance.

Advances in Indicator Technology

Recent developments have expanded chemical indicator capabilities beyond traditional applications. Nanomaterial-based indicators incorporate gold nanoparticles, quantum dots, or carbon nanomaterials to achieve enhanced sensitivity and multiparameter detection. These advanced indicators can detect target substances at concentrations as low as parts per billion, opening applications in trace contaminant detection and early disease diagnosis.

Smart packaging indicators now integrate time-temperature indicators with gas sensors to provide comprehensive food quality monitoring. These systems track cumulative temperature exposure and detect gases like carbon dioxide, ammonia, and hydrogen sulfide that signal microbial growth, offering more reliable spoilage detection than static expiration dates.

Digital integration represents another frontier, with smartphone-readable indicators that use computer vision algorithms to interpret color changes quantitatively. These systems photograph indicator responses and convert color data into precise numerical values, bridging the gap between simple visual indicators and laboratory instrumentation while maintaining field portability.

Biodegradable and environmentally friendly indicators address sustainability concerns associated with synthetic dyes. Natural pigments from plants like red cabbage, turmeric, and beetroot provide pH indication without environmental persistence, though they generally offer less stability and narrower application ranges than synthetic alternatives.

Best Practices for Indicator Use

Maximizing chemical indicator effectiveness requires attention to procedural details:

- Calibrate with standards: When possible, verify indicator responses using solutions of known values to confirm proper function

- Use minimal indicator quantities: Excessive indicator can alter solution chemistry; typically 2-3 drops per 50 mL suffices for most titrations

- Observe under consistent lighting: Color perception varies with illumination; white backgrounds and standardized lighting improve consistency

- Document storage conditions: Record preparation dates and storage environments to track indicator degradation

- Run controls: Include blank samples or positive/negative controls to verify indicator sensitivity and rule out contamination

For sterilization indicators specifically, healthcare facilities should follow manufacturer instructions precisely and maintain validation records. The Joint Commission and other regulatory bodies require documentation demonstrating indicator performance meets specifications, including periodic biological indicator challenges to confirm sterilization efficacy correlates with chemical indicator responses.

English

English русский

русский Français

Français Español

Español bahasa Indonesia

bahasa Indonesia Deutsch

Deutsch عربى

عربى 中文简体

中文简体